- Oct 9, 2025

Scaling Web Apps - Queueing

In this article, we will first discuss what can go wrong with traditional web applications architecture. Specifically, when our application calls internal or external services directly. Then, we'll talk about how to solve these problems with the introduction of a queue. Let' begin.

What Can Go Wrong?

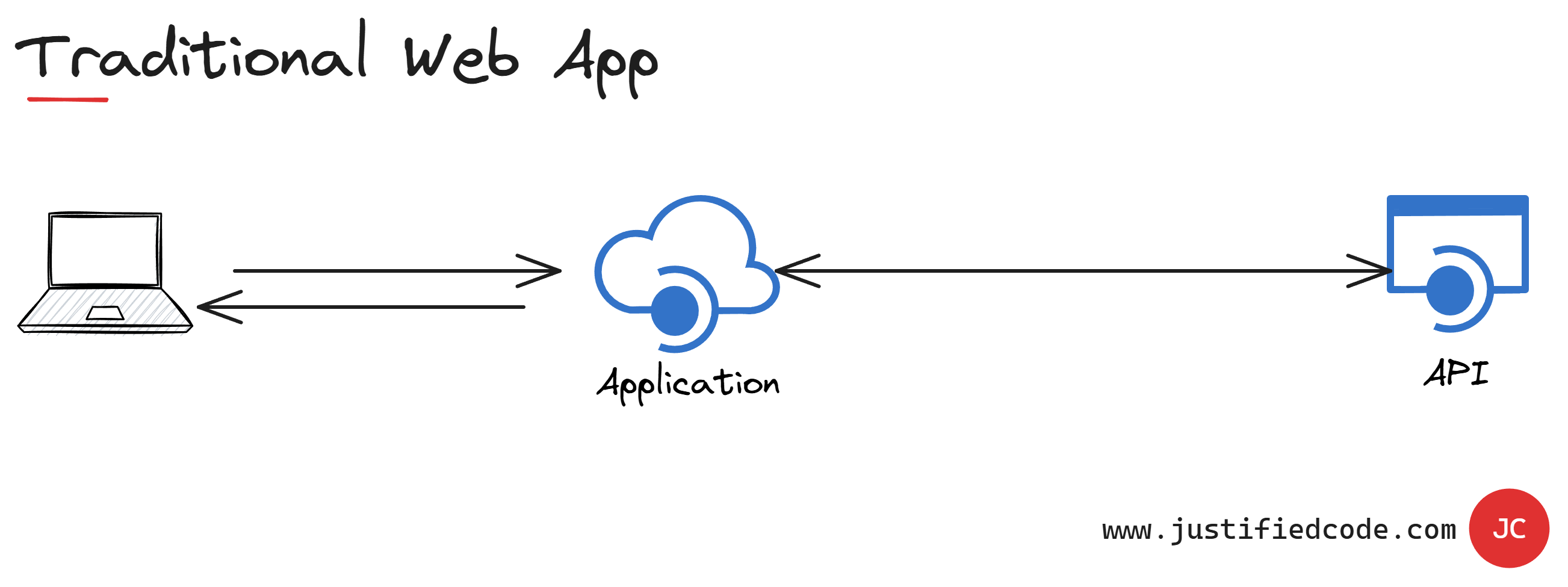

Let's start with an overview of a traditional web application calling an internal or external API directly. The API that the Application is calling could be part of the same solution, or, it could be a third-party API.

The API gets called by the Application to execute some transactions or retrieve information. If it's a third-party API, it is probably also called by other applications we don't know about. Thus, it's impossible to predict the amount of calls that are being made to that API, resulting in a variable load.

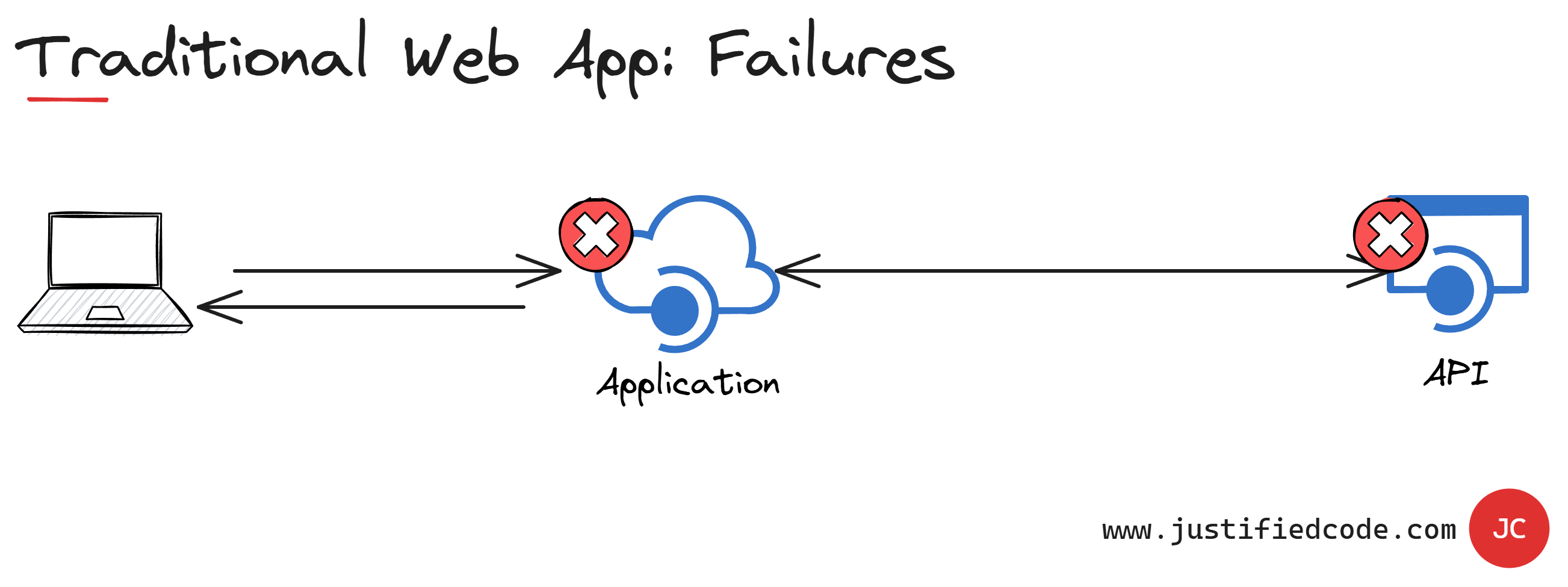

This could cause the API to become overloaded, as it can't handle the amount of requests coming in, which usually leads to failure of the API, which means that parts of our Application won't function properly anymore, or even the whole Application becoming not available.

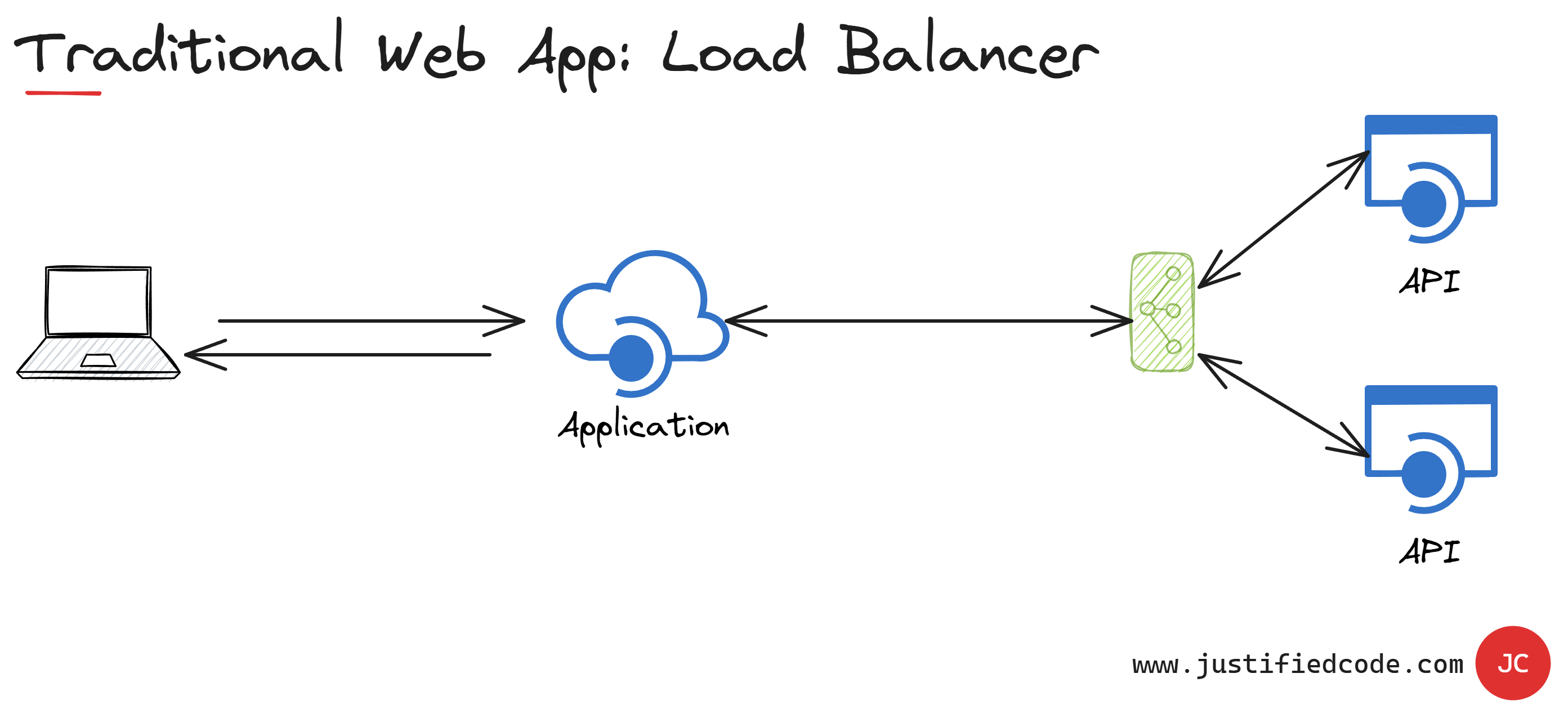

If this isn't a third-party API, we could try to solve this by scaling up it's capacity, or maybe by instantiating another instance of the API, and putting a load balancer in front of the instances.

However, it is still very hard to predict the traffic that will be thrown at the API. Therefore, this solution could still fail because we don't know how much capacity the API needs, leading to the Application becoming unable to scale.

So the best thing you can do is to scale for the maximum load that you think could be thrown at the API. The problem here is you will be increasing the costs of the application. Also, wasting resources since the scaled API won't be needed all the time, they are only needed when the API is under high load.

Decoupling with Queues

Now we have seen the trouble with traditional web applications or what we call the request response model. What's the alternative? The alternative is to decouple the individual components from one another.

We do this in a way that doesn't force the components to become coupled in the request. We want low coupled asynchronous communication that escapes the request response model. This is usually achieved with message queues.

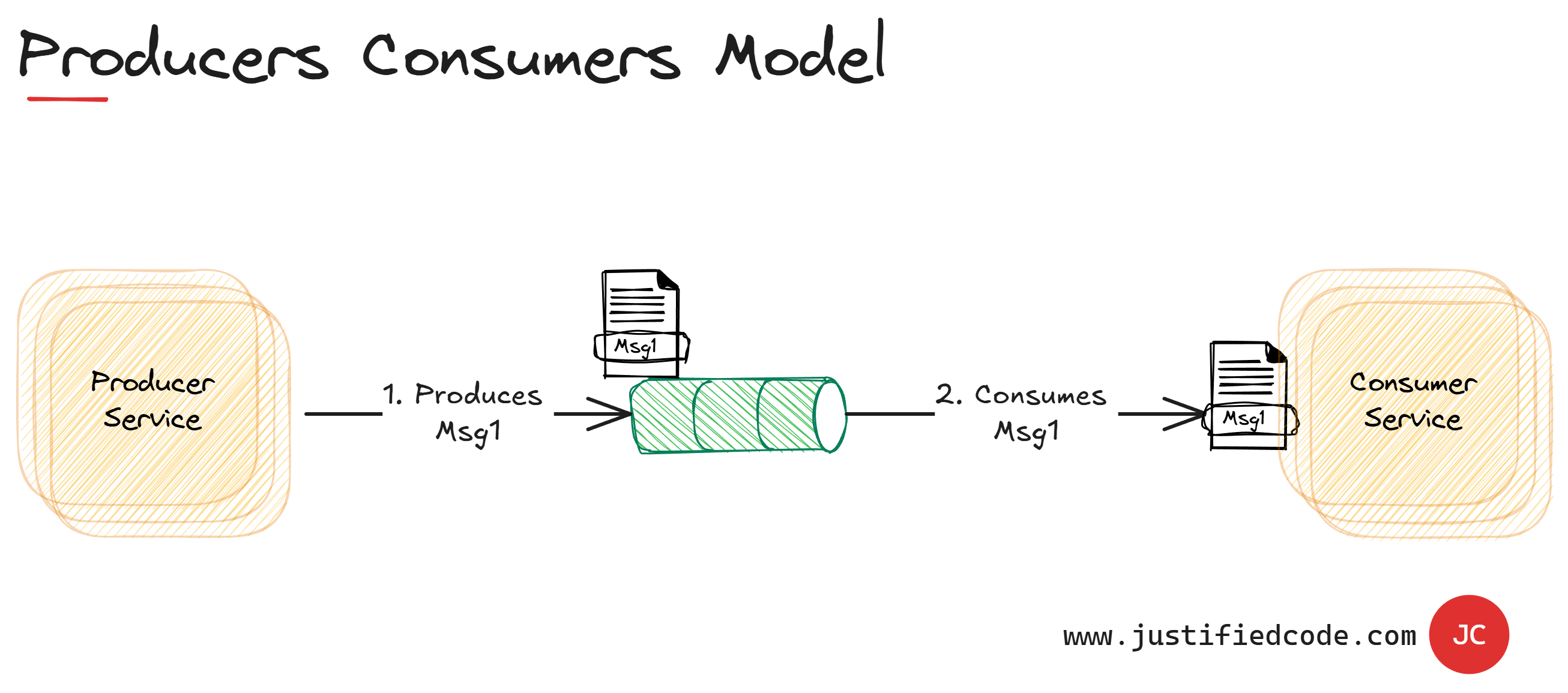

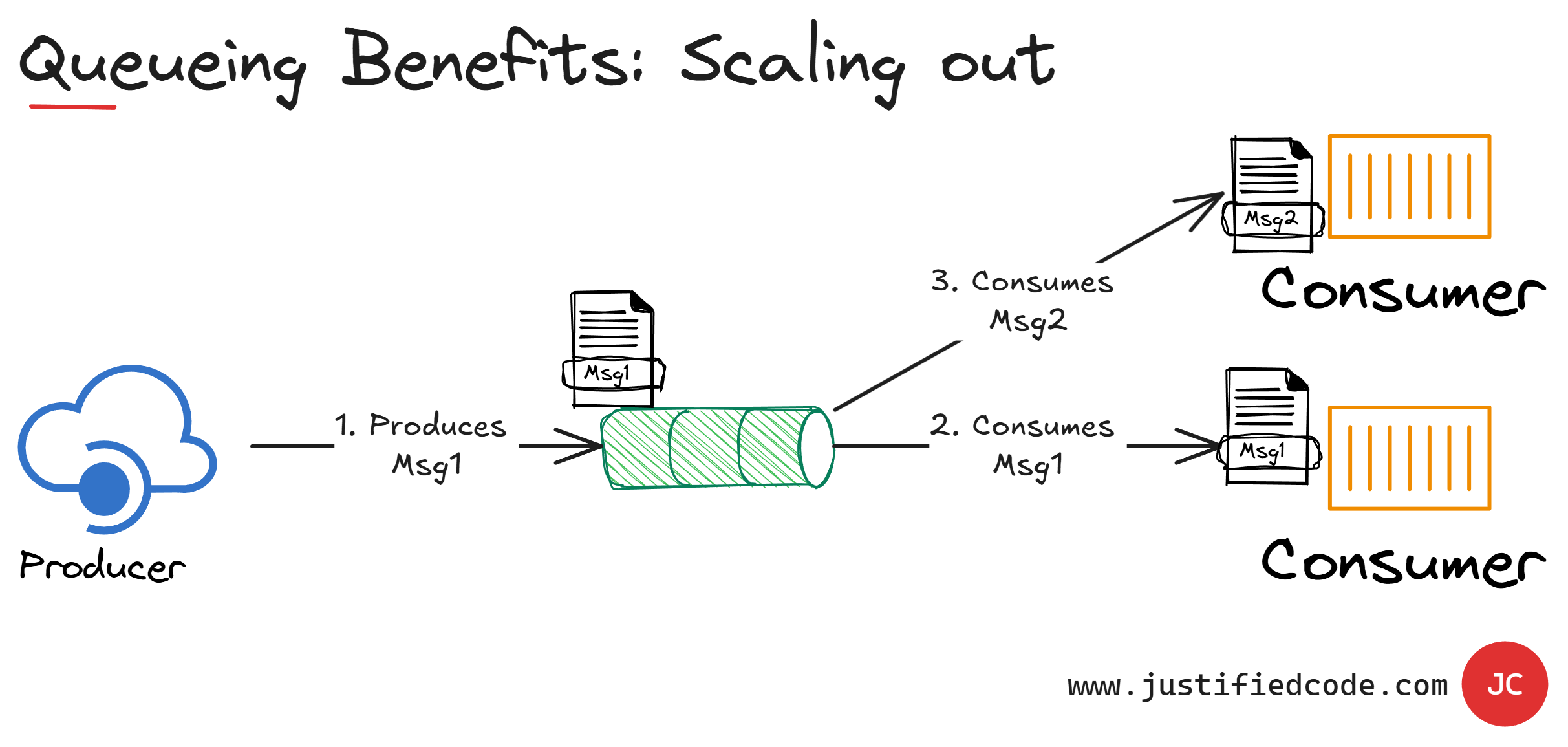

A message in this context means the data transported between two applications or with two application components. The basic architecture of the message queues is simple. There are client application components named producers that create messages and deliver them to the message queue.

Other application components called consumers are connected to the queue and get the messages to be processed. Messages placed into the queue are stored until the consumer retrieves them.

Message queues provide an asynchronous communication protocol. The component that puts a message into a message queue doesn't require an immediate response to continue processing.

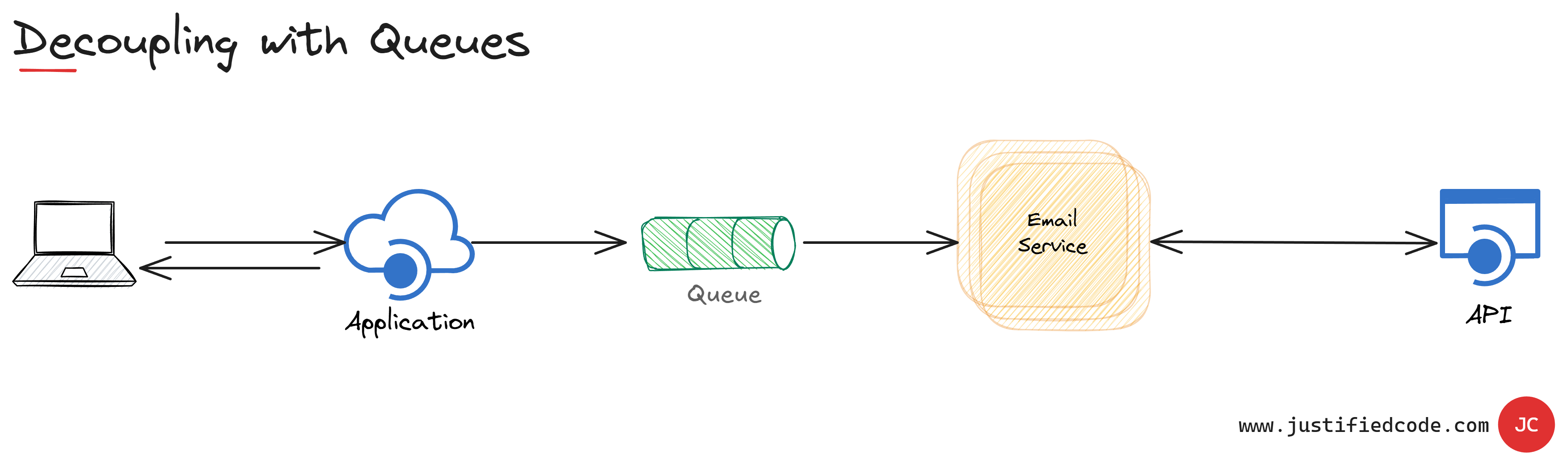

Email is probably the best example of asynchronous messaging. When an email is sent, the sender (Application) can continue processing other things without an immediate response from the receiver (Email Service).

This way of handling messages decouples the producer (Application) from the consumer (Email Service). The producer and the consumer of the message do not need to interact with the message queue at the same time.

This allows the ability to absorb additional requests without failing. The requests are written to the queue as fast as possible, but on the processing end, they are processed as fast as possible too.

The worst thing that would happen is to have many pending requests (pending emails) in the queue that should be eventually processed. The queue status can be monitored and if too many messages are waiting in the queue, we can spin additional processing components to handle them.

Conversely, if the queue is fairly empty we can power them down to save resources and money. The queue also helps with redundancy. If the processing component fails, the unprocessed messages are still in the queue and will be processed later.

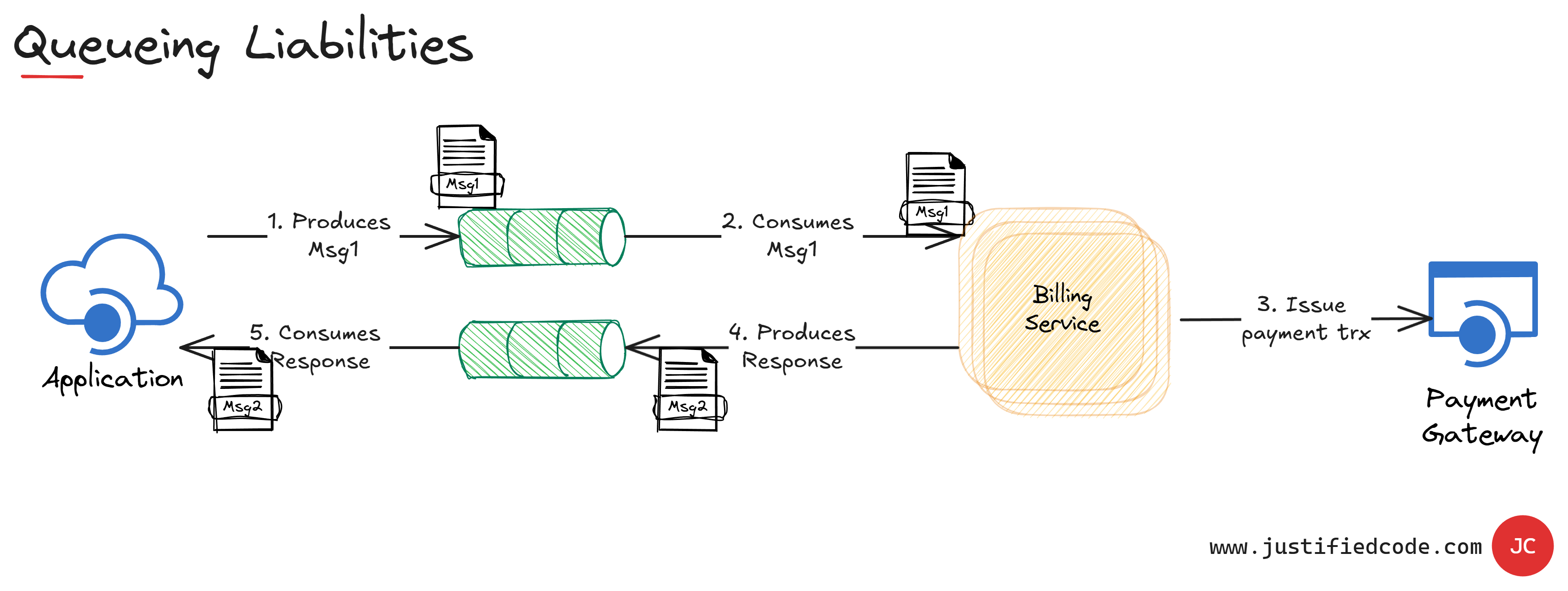

However, the message queues have several liabilities. The queue that transfers the message from the producer to the consumer is a one-way channel. When the processing result of a consumer app is required to be tracked, we need an additional queue to get the response back to the producer.

Effectively, the producer becomes the consumer as well. The requesting component places the message in a queue and then periodically polls the response queue to check if the message is processed.

This certainly adds complexity to our architecture. The queue mechanism has to be performant enough not to become a bottleneck in itself. It also needs persistence mechanisms to survive machine failures and not to lose any pending messages.

Next Step

Want to go deeper? Grab the free PDF guide on the Competing Consumers Pattern. It includes the problem, the solution, trade-offs, when to use the pattern and when to avoid it, system benefits and a real-world use case.