- Sep 4, 2025

Database Storage Locking

The data storage is one of the most important bottlenecks in our application architecture.

All web applications have some kind of storage in place to read from or to write to. Usually it has the form of a relational database that sits in one of the servers.

The idea is that we need persistent storage to be able to store information that will survive between user interactions. If our user logs out and then logs in a week, she will expect her data to be there.

Relational Databases

The basic elements of relational databases are tables or relations, hence the name relational databases. Tables are representations of entities in a tabular form with columns and rows. The columns are the fields and the rows contain the values for the entity instance.

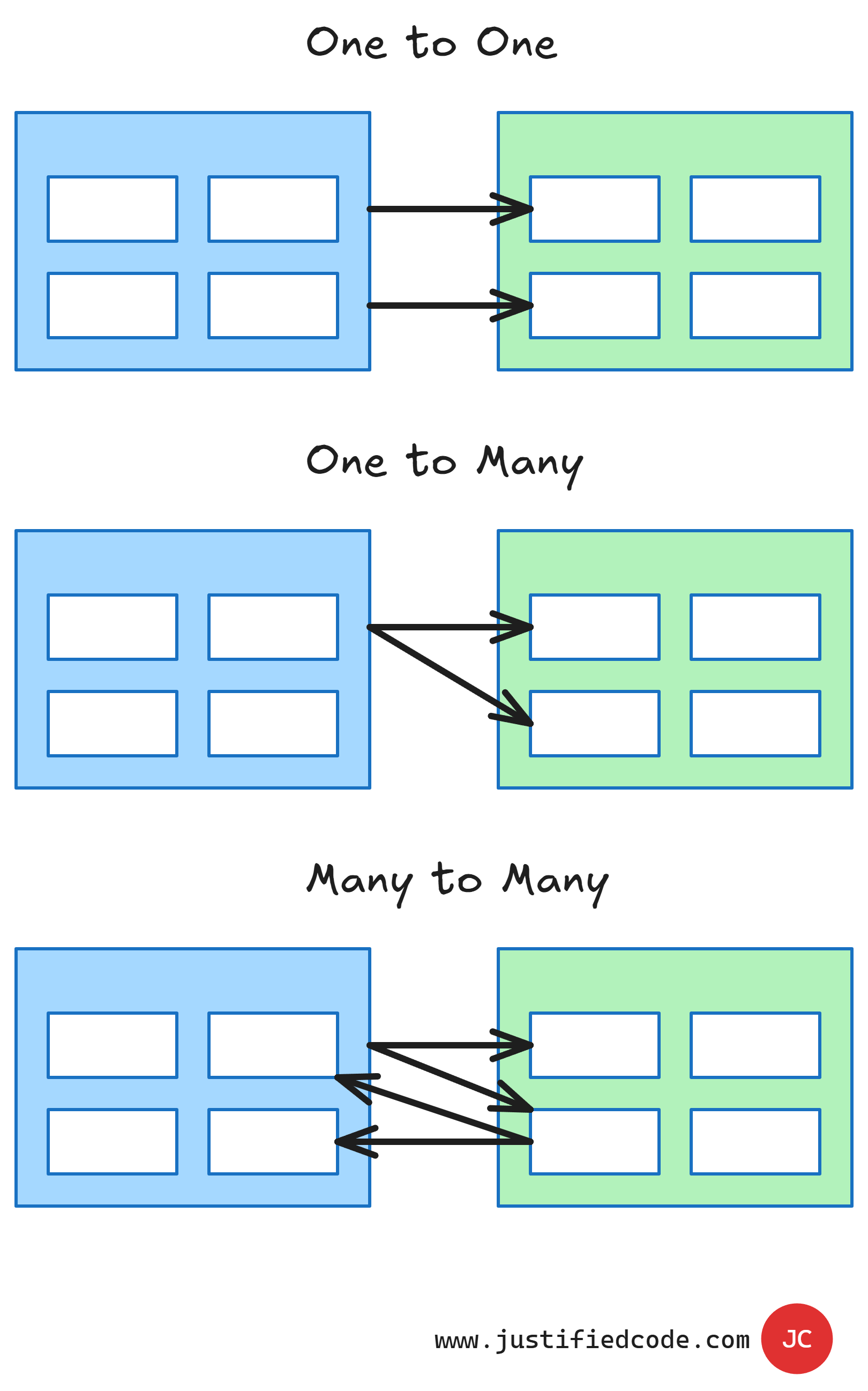

The rows are also called records. The tables themselves can form relationships between the columns in a single table or between different tables. There can be one to one relationships, one to many relationships, or many to many relationships. Here is an image to illustrate this.

The relationships exist to make sure that the data is consistent and not duplicated across the database and also to ensure the integrity of the data. The relational databases exhibit properties better known for the acronym ACID. Following is a simple description of each.

A stands for atomicity.

It means that the relational databases allow multiple operations to be done as a single operation that it can either succeed or fail. If it fails, all the operations roll back to the previous state before the first operation was done. This avoids leaving partial changes to the data when errors happen.

C stands for consistency.

A consistent database ensures that a data change would move the database from one valid state to another valid state. It prevents inconsistent results such as half of the database records updated with new values and the other half still showing the old data.

This is a very desirable property of a database, but this is the one that makes our database very hard to scale as we gonna see later.

I stands for isolation.

It means that all the operations are done as if the application is the only process accessing the database. In reality, there are usually many processes reading from and writing to a single database, but each one of them behaves as if it were the only one.

In other words, the database shields us from the effects of other processes changing the data that is shared between all of them. This beneficial effect hinders scalability as well.

D stands for durability.

It means that once the database transaction is committed, it will be recorded even if the database crashes. This is usually done by having a separate transaction log for committed operations that can be reproduced again if need be.

The Problem

ACID properties are very useful, but the main problem is that two of them, consistency and isolation, seriously hamper scalability.

Why? The answer lies more in the way relational databases are implemented, not in the way they are supposed to. Most relational databases implement consistency and isolation by the means of locking.

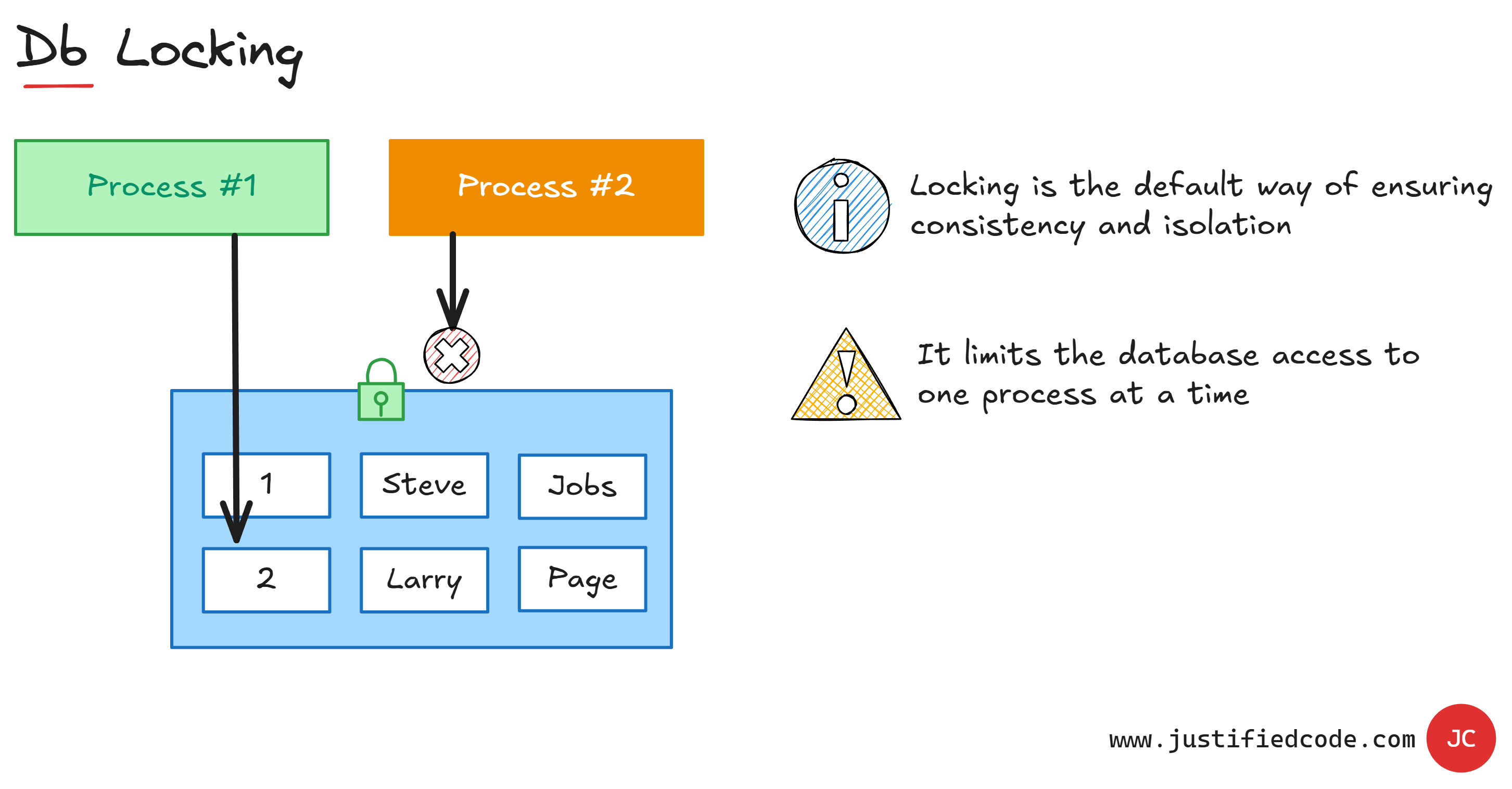

As you see, the process #1 that changes the data acquires a lock on the data that blocks other processes from changing the data until the previous process has finished.

Though this effectively assures data consistency, it has all the properties of a serious bottleneck. When using locking, only one process can change the data at a single point of time. To make it worse, the reads operations are locked too. Also, non-trivial transactions require a substantial amount of locking, degrading the database throughput even more.

Read/Write Complications

When we need increased scalability, mixing read and write operations in a single database creates complications. Relational databases enforce relationships to minimize data duplication and enforce data consistency.

This means using the same relational data model with related tables to both update the model and to make queries to that same model. However, the necessities for read and write operations are very different.

Read operations usually have to be quicker than the write operations. Also can be done using different search criteria, returning a single row or a very large amount of rows.

Write operations are usually restricted in scope to a single element and may take a longer time to finish.

Having both read and write operations on the same set of data is not efficient. Our database either favors updates or favors queries. The indexes built to speed up read queries are different than the indexes used to do updates.

The first consequence of sharing the same database for reads and updates is the compromise that we make to accommodate two different sets of operations without optimizing for either of them.

Remember the database locking is used to force isolation where multiple processes access the same data. So what happens when a read query and a write operation are issued at the same time? Enter the world of transaction levels.

Transaction Levels

The transaction levels defines how isolated those two operations are.

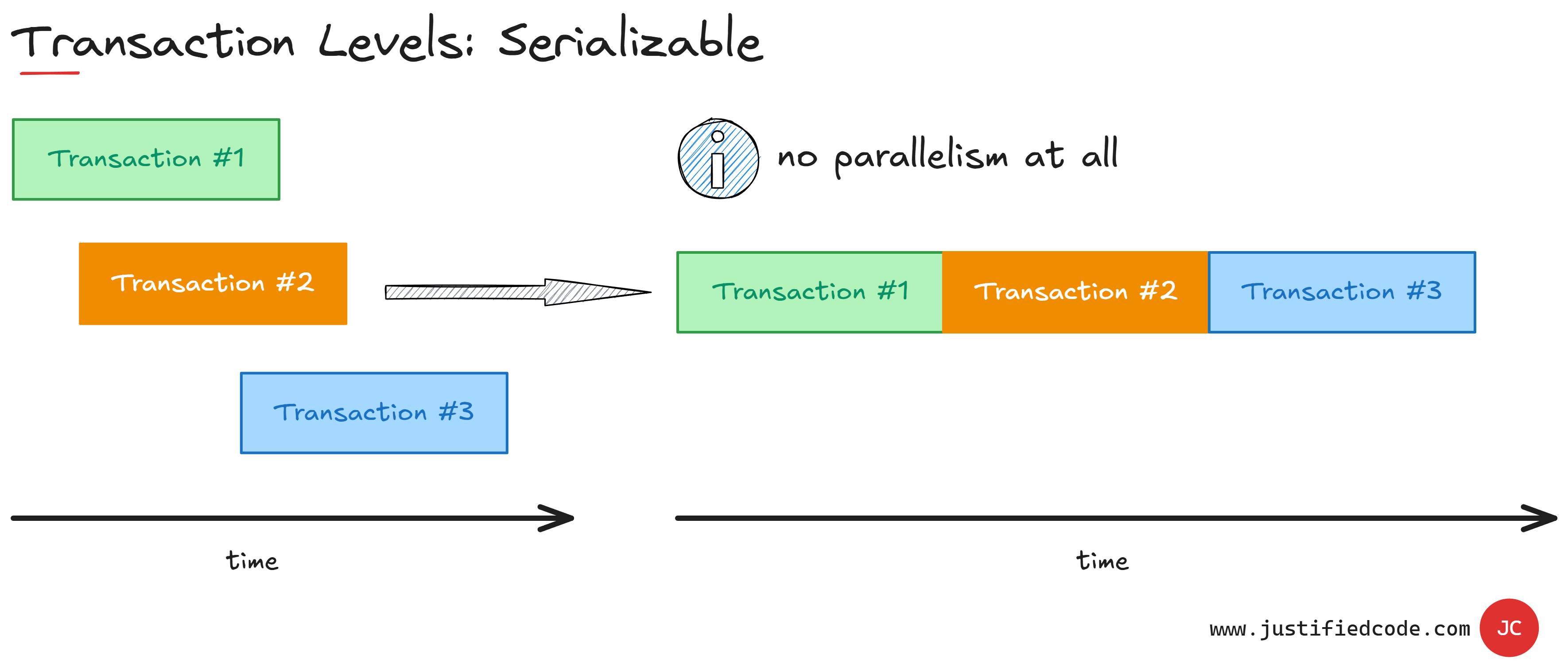

Serializable

The most isolated transaction level is called serializable. It means that all the transactions are done as if they were issued one after another, without any parallel operations.

We have maximum consistency and isolation, but at the expense of reducing the performance of our database. Serializable isolation is usually done by using exclusive locks for reads and writes.

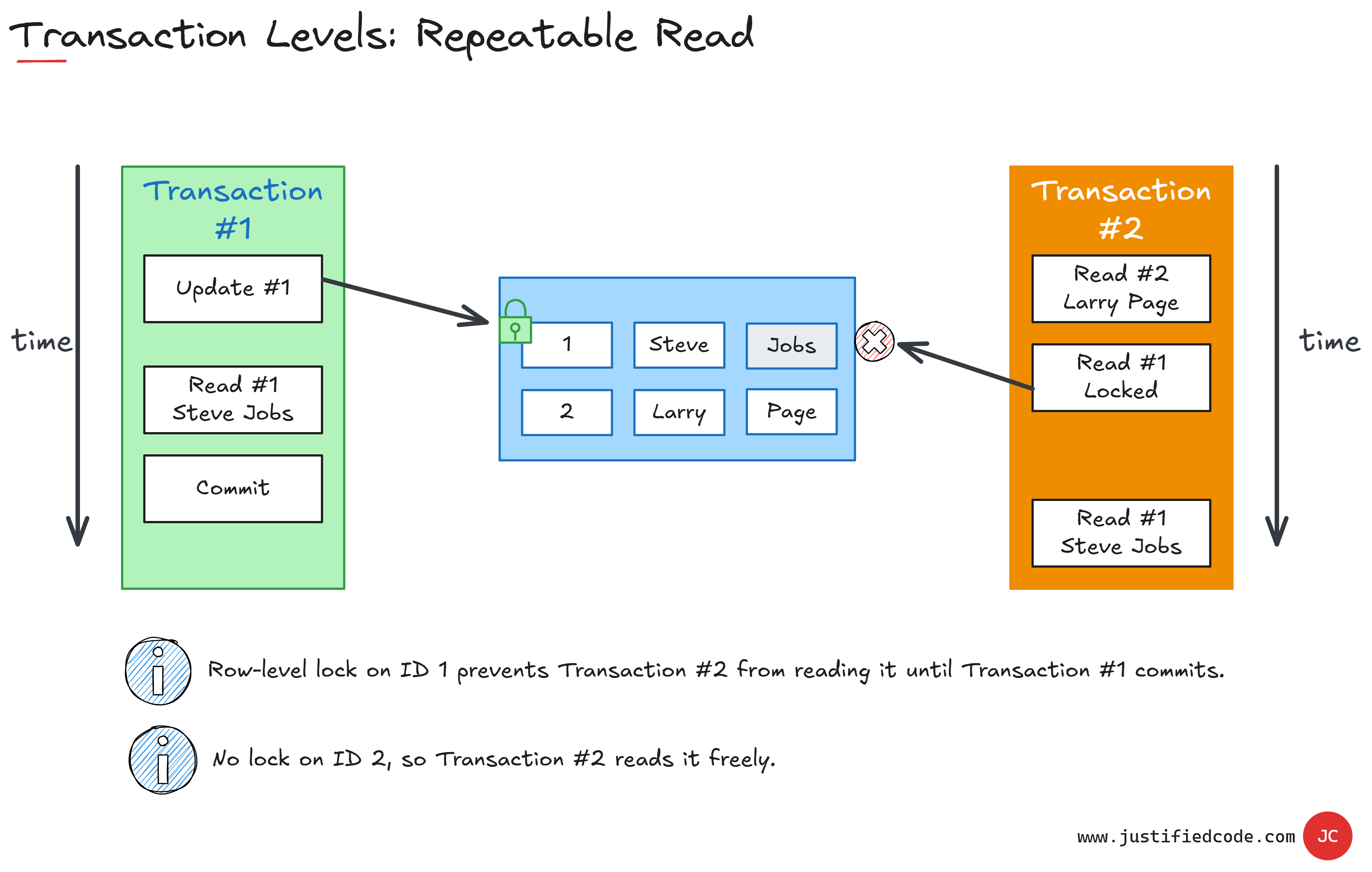

Repeatable Read

Relaxing the restrictions a little bit, we have repeatable read isolation level. The first one that allows for parallel transactions. It locks read and write during a single transaction. It does so by locking any processed rows in the tables that the transactions touches.

As its name reveals, it ensures that if we read twice during a transaction we will have two identical reads. In this case the second transaction, orange, read operation #2 is allowed to be processed, but the read operation #1 is locked. It's delayed until the first transaction, the green one, has finished and thus released its lock on the row.

However, we can still have phantom reads. Phantom reads are wide range queries such as select count(1) that return data outside a current transaction scope.

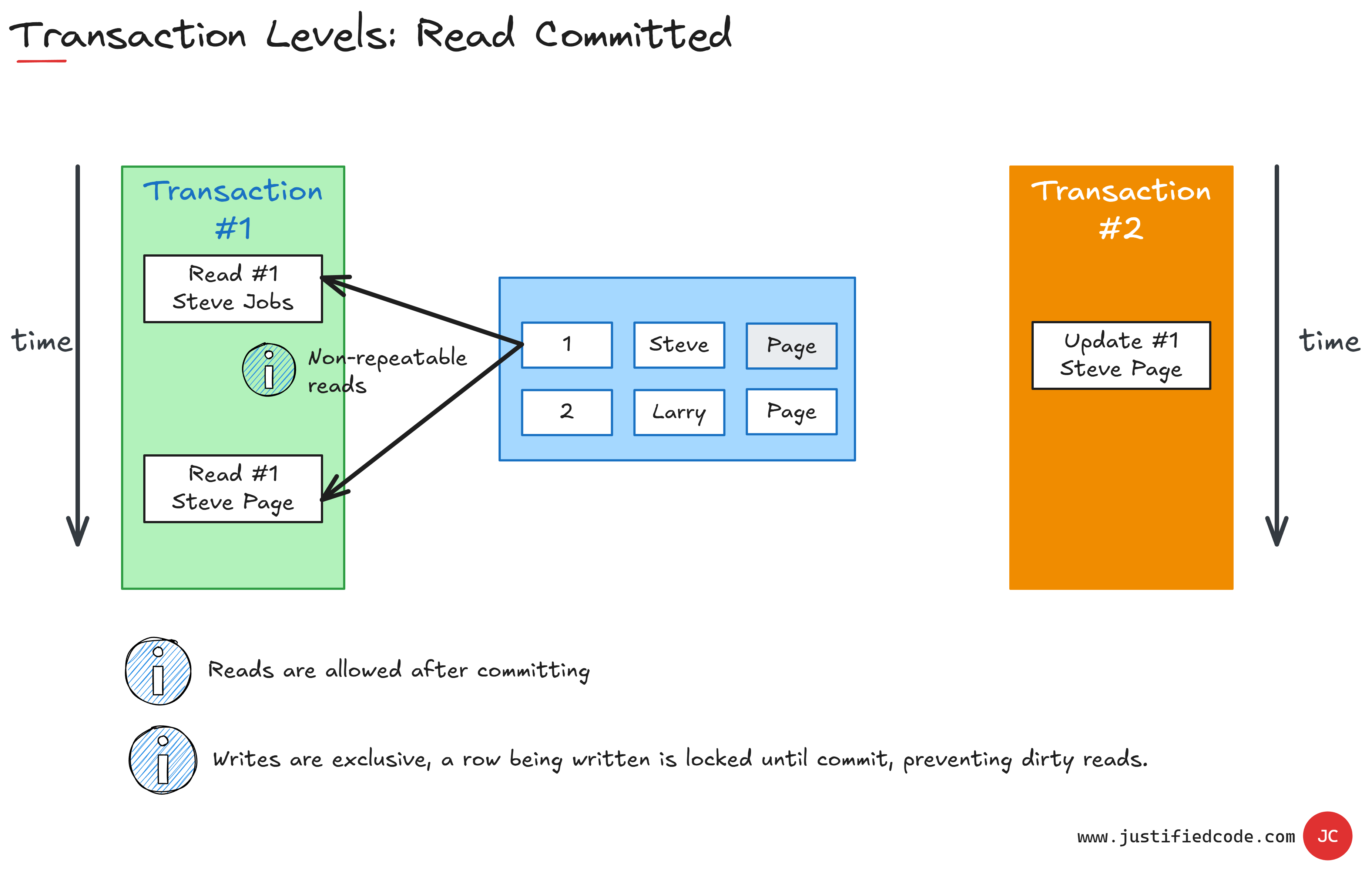

Read Committed

If we reduce the isolation level even more, we get read committed isolation level. It means that the data we read is the data that has been committed so we cannot read uncommitted or in-progress data until the transaction has been done.

Write operations are still exclusive to a single transaction at a time, but we cannot guarantee repeatable reads during the transaction. Then transaction can begin and finish between the reads. So in this case we have read two different values for the row #1 because there was one orange transaction #2 in the middle of transaction #1.

Read Uncommitted

The least isolated database level is called read uncommitted. It basically allows to read data at any point. We can read dirty data, but in exchange we get maximum parallelism for the read queries.

That's the most dangerous isolation level, thus i am not doing a diagram. A good call is to keep the transaction level set to the default value for each database vendor. Here is the list:

Default isolation levels in popular RDBMS

Oracle: Read Committed

SQL Server: Read Committed

MySQL (InnoDB): Repeatable Read

PostgreSQL: Read Committed

Next Steps

The lesson here is that using the same database for reads and writes, by nature, causes these operations to wait for one another, more or less, depending on the isolation level.

In Part 2 article, we will tackle the cure for the read-write complications. You don't want to wait? Good. Head to the Web Applications Scalability course where I break all the 5 components of scalability down while annotating every neat diagram with a Pencil, sharing raw experience from the field you won’t find anywhere else.